On writing about another culture

“When we understand each other's stories, we understand everything a little better—even ourselves.”

—Someplace to be Flying, Charles de Lint

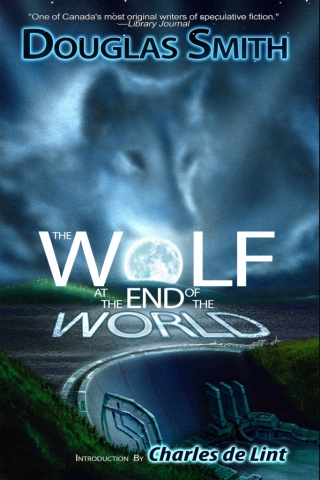

This will be a long post, but for me, it's an important one. I'm basing this post on the afterword that I include in my new novel, The Wolf at the End of the World. However, since a potential reader, especially a First Nations reader, may have concerns over the issue I address here (and therefore not read the book), I'm posting that afterword here.

On the Origin of The Wolf at the End of the World

My intent for writing this post is primarily to address a fear I had about writing The Wolf at the End of the World. But before I can get into that, I need to first talk about the book's genesis.

The first story I wrote (and sold) professionally was the novelette “Spirit Dance.” In it, we first meet my shapeshifting species, the Heroka, as well as my hero, Gwyn Blaidd and many of the other characters of The Wolf. That story takes place five years before the events in The Wolf. “Spirit Dance” was my first professional sale. It appeared in the anthology, Tesseracts6 in 1997, was a finalist for the Aurora Award in 1998, and won the Aurora Award in 2001 when it was translated into French. It’s been republished seven times in English and translated another sixteen times. Yes, the story totally rocks, and you should check it out.

I always planned to revisit the world and characters of “Spirit Dance,” so when I finally decided to write my first novel, continuing Gwyn’s story was an obvious choice.

On Writing About Another Culture

Now to my fear about writing The Wolf at the End of the World. I’m a white male of European descent (English, Welsh, Irish) who is writing about Cree and Ojibwe culture, traditions, and beliefs. Any author who writes about a current culture other than their own risks being accused of cultural appropriation.

That risk is even greater if the writer belongs to the majority that has traditionally held power in their society and is writing about a minority group in that society. It becomes greater still when that majority has oppressed that minority for nearly a quarter of a millennium, as the First Nations people have been since the Europeans first arrived in this land. My ancestors stole their land, broke treaty after treaty, and introduced programs and policies consciously designed to destroy their rich and unique culture and way of life.

Residential Schools

Perhaps the most egregious wrong perpetrated against our First Nations was the residential school system mentioned by my Ojibwe character, Ed Two Rivers, in this book, in which the Canadian government and various churches engaged in a premeditated program and formal policy of cultural genocide. The publicly stated goal was to assimilate the “Indian” into Canadian society (meaning white European culture), but the program was designed (in a federal minister’s own words in the 1920’s) “to kill the Indian in the child.”

The residential school system involved the forced removal of First Nations children as young as six years old from their parents and homes, and their mandatory and permanent residence at boarding schools funded by the federal government and run by various Christian churches including the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Methodist, United, and Presbyterian. The abuses perpetrated on First Nations children in residential schools have been documented by the survivors of the system—thousands of cases of horrific physical, mental, and sexual abuse. The system began in 1892 and didn’t end until over a century later when the last school run by the federal government closed in 1996.

Amazingly and thankfully, despite the sad history of residential schools and continued government and cultural oppression, our indigenous people have persevered in finding ways to carry on their traditions and to bring their rich heritage to new generations, refusing to have their culture relegated to the past.

If you would like to learn more about this shameful chapter in Canada’s history, I’d recommend Basil H. Johnston’s book, Indian School Days, which relates his personal experiences in a residential school. Johnston is an Ojibwe writer, storyteller, language teacher, and scholar, and has received the Order of Ontario and Honorary Doctorates from the University of Toronto. His other books were also a wonderful research source for this novel (see bibliography). I’d also point you to the film “Unrepentant: Kevin Annett and Canada’s Genocide,” which is available on YouTube. I would also recommend the “Truth and Reconciliation” website.

Additional atrocities continue to be revealed, including the recent exposure of federal research experiments in various communities and residential schools where our government subjected First Nations people to forced malnutrition to study the effects.

Back to My Concern

So, yes, I’m a tad paranoid that I, as a white man of British descent writing a story that draws from the storytelling traditions and culture of the Cree and Ojibwe, might be accused of cultural appropriation.

I could respond by simply saying that if a writer must only write about characters who are the same as themselves and solely of their own culture, then literature would be a dull and anaemic creature. Shakespeare was not a Danish prince, nor Robert Louis Stevenson a peg-legged pirate. Bram Stoker was not a vampire, nor Isaac Asimov a robot. J. K. Rowling is not an adolescent boy wizard, and Stephen King is not a homicidal car or teenage girl with telekinetic powers.

But I’d be dodging a serious issue. So first, let me explain why I was drawn to Cree and Ojibwe traditions and stories for this book.

Why Cree and Ojibwe?

It started with my shapeshifter species, the Heroka. I wanted to create something different from a standard werewolf. Writers have been there, done that too many times. For one thing, I wanted the Heroka to include all animals, not just wolves. And I wanted them to be more than just another bunch of shapeshifters. As absurd as it may sound, I wanted my Heroka to be believable.

Well, okay—as believable as shapeshifters can be. For one thing, I wanted to downplay the shapeshifter element. I wanted the primary characteristic of the Heroka to be the bond they hold with their totem species, and to have that bond be complete—physical, mental, and spiritual. I wanted the very vitality of a Heroka to be tied to the vitality of their totem.

Why? Because the bigger message here, the theme of the book if you like, is a warning call about what we’re doing to our environment, to our natural resources, to the wilderness that once defined this land—the wilderness the animal species that call this country home depend upon for survival.

So if this story was going to be about environmental exploitation and animal habitat destruction by modern Western society, I needed a contrasting cultural view, one founded on a deep and abiding respect for the relationship that exists and has always existed between humans and nature, humans and animals—a relationship that our modern society has forgotten and forsaken. I wanted a belief system that was diametrically opposed to the European view that places humans and our needs at the top of the pyramid of life on Earth.

A Different and Beautiful World View

And I found it in the stories of our First Nations. The Cree spirit Wisakejack is the voice for those stories in this book, and if I could choose just one of his tales to demonstrate the dichotomy between the traditional beliefs of native people and modern society, and why the beliefs of the Cree and Anishinabe fit so perfectly with the Heroka and the theme of the book, it would be his story of the creation of the world that he relates to the boy Zach in Chapter 10.

First, Kitche Manitou created the four elements—earth, water, fire, and air—and from them made the world—the Sun, stars, Moon, and Earth. Then he created the orders of life. First plants, which needed the sun, air, water, and earth. Then the plant eaters, which need the plants. Then the meat eaters, which need the plant eaters. And finally, he created humans. We came last, because we need everything that Kitche Manitou created before us. Air, water, earth, sun, plants, animals. We are the most dependent of all of creation, making us the weakest of all orders of life, not the strongest.

My Heroka understand that relationship. They get it. They understand that—as Wisakejack told Zach—everything’s connected. Western society has forgotten that. We’ve forgotten that we are dependent on the land. Forgetting our connnection, we’ve lost it, too.

Now, I’m not saying these stories encompass all of aboriginal culture. First Nations people are diverse and express their beliefs in varied ways, plus a large number today are also urban dwellers. But many First Nations stories speak of the close connection between humans and animals and the land, and I believe those stories continue to have relevance.

On Research and Respect

So that’s why I chose to draw on the rich and wonderful stories and traditions of the Cree and Ojibwe in this book. But that’s only part of my response to any concerns a reader might have about cultural appropriation.

I researched. A lot. I read as much as I could about the ceremonies, beliefs, traditions, and histories of the Cree and Ojibwe. And I read the stories. Ever so many stories. Because, as Wisakejack also tells Jack, that’s how the People taught their children. At first, I found those stories very strange, but eventually I came to understand them, appreciate how they both entertained and educated, taught children about the dangerous harsh environment that they lived in, where starvation was only one bad hunt or one greedy hunter away.

I did more research. I stayed at an Ojibwe First Nations Reserve. I interviewed the chief and her mother. I visited three different reserve communities and talked to as many First Nations people as I could. I read more.

In short, I tried to do my homework as best as I could. I’ve included a bibliography of reference sources that I used. If you’re interested, I heartily recommend that you check them out and read the stories yourself, both to enjoy and to learn more about the culture.

Finally, I’ve treated the Cree and Ojibwe culture with reverence and respect wherever I’ve used it in this book. That wasn’t hard to do. The more I learned of the culture, the more I held it in reverence and respect.

Your Thoughts Are Welcome

So there’s my defence. I fell in love with the stories and the culture, and found in them the same core truth that is the theme of the book and the same vitality that drive the Heroka. I did my very best to make sure I got things right and as accurate as possible. And I treated that culture with respect.

If you’re Cree or Anishinabe or of any other First Nation, and you read The Wolf at the End of the World, I’d love to hear from you. Tell me what I got right. Tell me what I got wrong. Tell me what you thought.